"We are losing our attitude of wonder, of contemplation, of listening to creation and thus we no longer manage to interpret within it what Benedict XVI calls 'the rhythm of the love-story between God and man.'"

+ Pope Francis

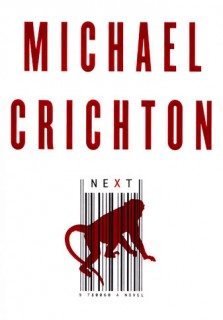

The primacy of the person and other lessons from Michael Crichton’s "Next"

Before the days of global quarantine, it had been a while since I’d found the time to read “for fun”, and even longer since I’d been glued to a real page-turner. But that’s exactly what Michael Crichton’s Next is. You know it’s good when you’re charging towards the end of a 500-plus page novel at three in the morning and slip off the end of the last chapter with a real sense of surprise that the whirlwind story is actually finished.

But it wasn’t finished for me. Next got me thinking about my response to it as a Catholic reader. What follows is meant to be part book review, part reflection on bioethics. Fitting for a novel starring some wonky hybrid animals, I suppose.

Next is the work of Michael Crichton, the mastermind whose movie-adapted Jurassic Park brought dinosaurs into our living-rooms. The author whose name has become synonymous with meticulously-researched sci-fi thrillers that border chillingly on social prophecy. Jurassic Park has always been one of my favorite movies (that’s for another post), which eventually led me to read some of Crichton’s novels. Having enjoyed Prey and Disclosure so much, I was surprised I’d never picked up Next when I spotted its fluorescent orange cover on our bookshelf a few weeks ago. Once I started, I was hooked.

Next is an interweaving of multiple storylines that center on issues of genetic research and modification, and their implications for the scientists, patients, lawyers, parents and countless others wrapped up in what turns out to be a supremely frightening web. The novel reads like a scrolling marquee of biological misadventures, each more terrifying than the last. We meet a dizzying cast of players: among others, a cancer survivor fighting to reclaim legal rights to his own cells, an ambitious young biotech worker who is moonlighting as a peddler of deadly gene therapies, a young boy and his mother on the run from armed cell-harvesters, and even a transgenic chimpanzee named Dave, who shares DNA with his geneticist “father”.

One of the more morally ambiguous characters is Dr. Robert Bellarmino, a bigwig at the National Institutes of Health, Baptist lay-pastor, and suave politician. Crichton uses him alternately as a mouthpiece for his own critical views on religious hypersensitivity to genetic engineering and as an example of the rampant lack of scruples often attendant on that engineering. Bellarmino is perhaps the best personification of the author’s—and by extension society’s—fundamental moral discomfort with the issue of genetic engineering, and bioethics in general.

One of the more morally ambiguous characters is Dr. Robert Bellarmino, a bigwig at the National Institutes of Health, Baptist lay-pastor, and suave politician. Crichton uses him alternately as a mouthpiece for his own critical views on religious hypersensitivity to genetic engineering and as an example of the rampant lack of scruples often attendant on that engineering. Bellarmino is perhaps the best personification of the author’s—and by extension society’s—fundamental moral discomfort with the issue of genetic engineering, and bioethics in general.

Bellarmino delivers a multi-page speech, delivered at a Congressional Biotechnology Prayer Breakfast, in which the doctor starts off with an eloquent and orthodox defense of the compatibility of Christianity with scientific endeavors and genetic engineering in general. He ends, however, by subtly transitioning into a tacit approval of using embryos and germ cells for the purposes of gene therapy research.

Bellarmino’s frequent invocation of Christianity’s directive of healing and alleviation of suffering as a justification for venturing into what he admits is “that most sensitive subject” comes off as sly and sanctimonious. And it seems that that’s what Crichton intends. After the speech, he has Bellarmino mentally congratulate himself on having so adeptly planted the seed of acceptance in the minds of his Christian audience members: “Five years ago, he did not use the word embryo. Now he did, cautiously and briefly.” An hour later, we see Bellarmino giving a diplomatically worded testimony in support of gene patenting to the House Select Committee on Genetics and Health. Crichton makes sure readers know that Bellarmino’s apparently balanced, impassive report is peppered with blatant untruths and belies his strong personal investment in the issue – Bellarmino is an aggressively unscrupulous pursuer of gene patents himself, even usurping the work of fellow researchers to reach his professional and financial aims.

“So what does Crichton really want us to think?”

The character of Dr. Bellarmino had me asking myself this question not infrequently throughout the novel. In the Author’s Note, Crichton comes clean about his personal persuasions regarding the issues treated in the book. Among them are these: Stop making some areas off-limits to genetic research, and stop patenting genes. The book makes a fairly clear case against gene patenting; besides solid arguments gleaned from extensive research, Crichton casts Bellarmino and other unsavory players as its supporters throughout the novel. But what about these “sensitive” areas of research? It seems odd that Crichton should choose a character as unsympathetic as Bellarmino to champion what he ultimately suggests is, in fact, his opinion: everything—presumably including human embryos—should be fair game for genetic manipulation.

Perhaps this wasn’t a deliberate literary choice, but rather a subconscious reflection of the author’s own lingering distaste for something which he, like so many others, had been railroaded into accepting as necessary for the “common good”. Tellingly, Crichton includes the following quote by William James at the beginning of the book: “The word ‘cause’ is an altar to an unknown god.” Understandably, Crichton remains discomfited by the idea of sacrificing the integrity and dignity of individual persons to some vague and too-easily corrupted deity.

Is Crichton guilty of some moral cowardice here? Perhaps, although his fence-sitting might be excused on the grounds of having produced a novel as nuanced and thought-provoking as Next. As a reader, Next left me in still greater awe of Crichton’s literary prowess. As a Christian, it left me rattled, and more than a little defensive. It’s all very well for fictional characters and even secular authors to never take a clear moral stand. But the truth is, Crichton’s Dr. Bellarmino represents the current thinking of more Christians than we’d care to admit.

What exactly is this thinking? Self-deceiving at best and gravely dangerous at worst, it’s the idea that the good of the many (or at least the promise of it through scientific advancement) ultimately trumps the inherent inviolacy of any one person. Tellingly, opinion polls have shown that among Christians—including Catholics—moral opposition to abortion is much stronger than moral opposition to embryonic stem cell research. Since abortion tends to be viewed as a private issue, with less clear benefit to society as a whole, while stem cell research is often perceived as a useful tool in reaching public health goals, this discrepancy would seem to indicate the willingness of many Christians to overlook trespasses on human dignity when those actions stand to benefit the public.

Disturbingly, this way of thinking often twists the rhetoric of Christianity to serve its own ends. Bellarmino’s appeal to his Congressional audience exemplifies this tactic in its most sophistic form: “Our Lord Jesus made men walk again. Does that mean we should not do likewise, if we can?”

In an address to a general assembly of the World Medical Association in 1983, Pope Saint John Paul II warned against this particular pitfall of medical philosophy. Rather than parse out our late Holy Father’s wisdom, I choose to present the following extract in its totality:

What must be established definitively is whether medicine is indeed at the service of the human person, of his dignity, of what he has of the unique and of the transcendent, or whether medicine is considered first of all as the agent of the community, at the service of the interests of those in good health, to whom the care of the sick would be subordinated. Now medical morality has always defined itself, since the days of Hippocrates, as respect and protection of the human person. What is involved here is much more than the preservation of a traditional deontology; it is respect for a concept of medicine which is valid for men of all times, which safeguards the man of tomorrow, thanks to the value it attaches to the human person who is a subject of rights and of duties, and never an object to be used for other ends, not even some self‑styled social good.

Whether the “community” his Holiness refers to is composed of the sick desperate for cures or of the healthy that profit from their desperation seems immaterial. Next shows us the dangerous domino effects of decisions that all, in some way, place the dignity of the individual secondary to group interests. Ecology assures of us of the interconnectedness of all life. Even if Crichton’s Bellarmino muddies the moral waters, the message should still be clear for Christian readers: Humanitarianism can never be reliably established on the denial of any one instance of humanity.

Eleanor Carrano graduated with a B.S. in Biology from the University of Dallas ('15) and earned her M.S. in Geological Sciences from San Diego State University ('20). In her writings, Ms. Carrano seeks to promote a holistic approach to environmental conservation and to constructively marry issues of faith and science. In her free-time, Ms. Carrano enjoys traveling, spending time with her animals, and playing the piano.

Eleanor Carrano graduated with a B.S. in Biology from the University of Dallas ('15) and earned her M.S. in Geological Sciences from San Diego State University ('20). In her writings, Ms. Carrano seeks to promote a holistic approach to environmental conservation and to constructively marry issues of faith and science. In her free-time, Ms. Carrano enjoys traveling, spending time with her animals, and playing the piano.